Eating in Paris: The Basics

I've done my best to keep this up to date in the post-pandemic (or wherever we are) world. Links to restaurants and other things should be more or less up to date.

Why go to Paris if you're not going to eat? Every once in a while, big newspapers and magazines in the US will run stories about the 3 or 4 "remaining affordable bistros in Paris," and they proceed to list places that cost upwards of 50 to 75 euros per person. This is utter, unabashed balderdash, mostly meant to show off how plugged into the local scene the article's author is. And in fact, it shows the absolute contrary. The simple fact is that there are hundreds and hundreds of astonishingly good, inexpensive restaurants in Paris, and it's not difficult to find truly great meals in the 20 to 30 euro range. You can even find really good food for less than that (and my favorite restaurant in the world is still well under 20 euros). All you have to do is read Tom's Guide, or, if you want to strike out on your own, just walk around a little, and avoid the big busy streets (but I can't imagine why you wouldn't want to read Tom's Guide). Go around the corner; peek inside a courtyard. Hop on the metro and choose a stop at random to get off at. You'll find something good. Every restaurant in Paris will display their menu out front, so you can walk around and inform yourself before you choose. Be daring, be bold, be assertive—eat.

(And a New York Times article about restaurants in Paris that date back to the 19th century includes many which have been in Tom's Guide for almost that long [well, not quite]).

Why go to Paris if you're not going to eat? Every once in a while, big newspapers and magazines in the US will run stories about the 3 or 4 "remaining affordable bistros in Paris," and they proceed to list places that cost upwards of 50 to 75 euros per person. This is utter, unabashed balderdash, mostly meant to show off how plugged into the local scene the article's author is. And in fact, it shows the absolute contrary. The simple fact is that there are hundreds and hundreds of astonishingly good, inexpensive restaurants in Paris, and it's not difficult to find truly great meals in the 20 to 30 euro range. You can even find really good food for less than that (and my favorite restaurant in the world is still well under 20 euros). All you have to do is read Tom's Guide, or, if you want to strike out on your own, just walk around a little, and avoid the big busy streets (but I can't imagine why you wouldn't want to read Tom's Guide). Go around the corner; peek inside a courtyard. Hop on the metro and choose a stop at random to get off at. You'll find something good. Every restaurant in Paris will display their menu out front, so you can walk around and inform yourself before you choose. Be daring, be bold, be assertive—eat.

(And a New York Times article about restaurants in Paris that date back to the 19th century includes many which have been in Tom's Guide for almost that long [well, not quite]).

Why go to Paris if you're not going to eat?

There are more sophisticated, strange, interesting, frightening, inexpensive, alternative, and/or charming restaurants in Paris than you can possibly imagine.

If you hadn't waited so long to go to Paris, for example, you could have dined at the Casa Miguel, on the Rue St. Georges up near Pigalle. This is no longer open, but it was run for the longest time by a woman  who was 88 years old if she was a day. Mme Miguel did all the cooking and most of the serving, and maybe that's how she kept her costs down: hers was the cheapest restaurant in France, with a Guinness certificate in the window to prove it. Last time I was there a three-course meal including beverage was only 5 francs (that's less than 1 euro)—and I'm not kidding. You would go there and expect to be seated next to clochards (really). I'm not sure, but I think Mme Miguel ran the place really to feed a lot of these homeless guys, most of whom, it turned out, were generally quite charming. It was really a trip. There was another unusual place we used to go to called Le Pendu (the Hanged Man) over in the 1st. There were absolutely no lights in the dining room; each table had a single candle on it, and each of the tables along the wall had a different small and gruesome painting of a hanged man right above it. You could barely make

who was 88 years old if she was a day. Mme Miguel did all the cooking and most of the serving, and maybe that's how she kept her costs down: hers was the cheapest restaurant in France, with a Guinness certificate in the window to prove it. Last time I was there a three-course meal including beverage was only 5 francs (that's less than 1 euro)—and I'm not kidding. You would go there and expect to be seated next to clochards (really). I'm not sure, but I think Mme Miguel ran the place really to feed a lot of these homeless guys, most of whom, it turned out, were generally quite charming. It was really a trip. There was another unusual place we used to go to called Le Pendu (the Hanged Man) over in the 1st. There were absolutely no lights in the dining room; each table had a single candle on it, and each of the tables along the wall had a different small and gruesome painting of a hanged man right above it. You could barely make  out the painting, and you could barely see your food (or the person across the table from you). It was quite sexy, actually. The thing is, there are scores of restaurants like this. Go find some more and then tell me about them. Most of the restaurants listed in these pages are inexpensive to moderate; there are a couple of big splurges. All of the ones listed here have something to recommend them—food, ambiance, location, people, price.

out the painting, and you could barely see your food (or the person across the table from you). It was quite sexy, actually. The thing is, there are scores of restaurants like this. Go find some more and then tell me about them. Most of the restaurants listed in these pages are inexpensive to moderate; there are a couple of big splurges. All of the ones listed here have something to recommend them—food, ambiance, location, people, price.

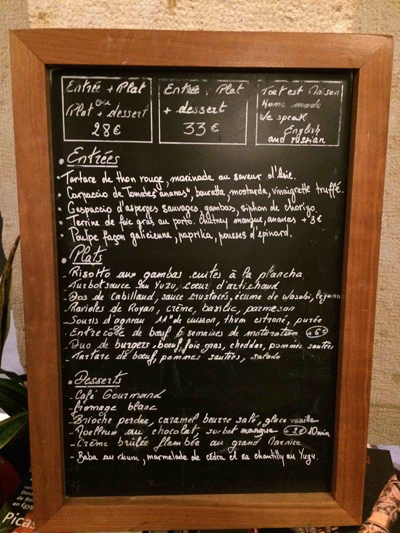

There are a couple of things to remember when in a French restaurant: except for really expensive ones, most will offer at least one form of menu or "prix fixe" (pree feeks), which is a menu where everyone pays the same price, and you get a limited choice of appetizer, main course, dessert, etc. It's usually much more economical than going "à la carte," in which you choose your whole meal in what amounts to the American style. Note that the "menu" option is much more common in France than it is in the U.S. (most restaurants you'll end up at will have at least one, although since the pandemic many restaurants are no longer offering a prix fixe, perhaps because for financial reasons), and that you'll eat very well this way—you shouldn't think of it as the cheap way out, for which you'll end up getting not very much or not very good food. Au contraire: you'll eat very well. Often restaurants will have "menus" at different price ranges, and the difference in price will correlate things such as the number of courses you get, and the kind of item on the menu. You can more or less always go "à la carte," of course, but check to see whether the things you want aren't actually on the menu at a lower price—you'll find that quite often they are, and that you can save sometimes as much as ten euros or more this way. Just listen to me: order from the prix fixe menu and I bet you'll like it. Also common is the menu of the day on a slate board that will be either hanging on the wall, or brought directly to your table and propped up on a chair or something. You'll also note that a lot of Parisian restaurants are located in really interesting buildings. As an example, check out Tom's Guide reader Colin's review of L'Auberge Nicolas Flamel below...) And reader Stuart G. from New York reminds us that not all great eating experiences take place where you'd necessarily think: "Many museums have cafes and restaurants that serve excellent food in remarkable settings. My favorite is the tearoom at the Musee D'Orsay. It was originally the First Class waiting room and

well this way—you shouldn't think of it as the cheap way out, for which you'll end up getting not very much or not very good food. Au contraire: you'll eat very well. Often restaurants will have "menus" at different price ranges, and the difference in price will correlate things such as the number of courses you get, and the kind of item on the menu. You can more or less always go "à la carte," of course, but check to see whether the things you want aren't actually on the menu at a lower price—you'll find that quite often they are, and that you can save sometimes as much as ten euros or more this way. Just listen to me: order from the prix fixe menu and I bet you'll like it. Also common is the menu of the day on a slate board that will be either hanging on the wall, or brought directly to your table and propped up on a chair or something. You'll also note that a lot of Parisian restaurants are located in really interesting buildings. As an example, check out Tom's Guide reader Colin's review of L'Auberge Nicolas Flamel below...) And reader Stuart G. from New York reminds us that not all great eating experiences take place where you'd necessarily think: "Many museums have cafes and restaurants that serve excellent food in remarkable settings. My favorite is the tearoom at the Musee D'Orsay. It was originally the First Class waiting room and  it's over the top ornate with amazing murals on the ceilings and huge crystal chandeliers. Don't miss it." (That's Stuart's photo at left.)

it's over the top ornate with amazing murals on the ceilings and huge crystal chandeliers. Don't miss it." (That's Stuart's photo at left.)

If you're going to a nice place, and especially on a weekend, make a reservation. If your French isn't great, don't worry. Try English if you must, but give your French a shot, too. You'll find people unexpectedly nice to you, especially if you follow the politeness tips here (hint: no matter what, always say "bonjour" before you say anything else). If you have a reservation, even if the place has empty tables, they will treat you significantly better, and at nice places the waiter or maître d' might even shake the hand of the person in whose name the reservation was made, since they'll consider you the host (but that doesn't stick you with the bill). Plus, it's just polite to reserve, since it helps the restaurant plan its shopping, its seating, and whatnot.

When you walk into a restaurant you will generally be greeted at the door, just as you would expect. Tell them how many people in your party, and if you have a preference about where you'd like to sit, tell them. Often you'll be asked if you would like an apéritif (a before-dinner drink). Have one. Most apéritifs aren't what you might be used to. Ask for a kir (black currant liqueur and white wine), a kir royal (same thing, but with champagne instead of white wine), an Americano (campari, vermouth, and club soda), or a Ricard (anise-flavored liqueur); or ask them what they have. Chill. You're going to enjoy yourself. (This photo of one of our courses at the Franco-Japanese restaurant Les Enfants Rouges was taken by my friend Ali.)

When you walk into a restaurant you will generally be greeted at the door, just as you would expect. Tell them how many people in your party, and if you have a preference about where you'd like to sit, tell them. Often you'll be asked if you would like an apéritif (a before-dinner drink). Have one. Most apéritifs aren't what you might be used to. Ask for a kir (black currant liqueur and white wine), a kir royal (same thing, but with champagne instead of white wine), an Americano (campari, vermouth, and club soda), or a Ricard (anise-flavored liqueur); or ask them what they have. Chill. You're going to enjoy yourself. (This photo of one of our courses at the Franco-Japanese restaurant Les Enfants Rouges was taken by my friend Ali.)

All the nonsense you've heard about French waiters being rude is just that: nonsense. A couple caveats, though. If you go to a bistro or brasserie, gruff service is part of the genre. It's not you; it's not them—this is just the way these restaurants go, so don't worry about it.  Some of the restaurants listed on the Left Bank and Right Bank pages are very fine, but you will not find there (or anywhere, for that matter) the obsequious service so annoying in a lot of American restaurants ("Hi, I'm Buffy, and I'll be taking care of you"). For the French, being a waiter or waitress is more like a career than it generally is in the U.S., and they take professionalism very seriously. You don't expect your dentist to say, "Hi, I'm Darrell, and I'll be taking care of your teeth today!" so the French feeling is, why should a waiter be silly and cloying? Service (tips) is virtually always included in the price of a meal in France (that's what the abbreviation S.C. means [service compris], and on some "menus" your beverage is, too, but that's not all that common (it'll say boisson comprise if it is, and there will be a list of choices). Even when service is included, it's always nice to leave a little something, especially if your waiter or waitress was especially good—a couple euros is a nice gesture. No one eats before 7:00, and that's still really early, and not many people really eat before 8:30 in the summer—think more like 9:00 or later. Virtually all restaurants accept whatever major credit card you may have. In fact, they'll have this neat little hand-held thing that they use to process your card; it's totally cool.

Some of the restaurants listed on the Left Bank and Right Bank pages are very fine, but you will not find there (or anywhere, for that matter) the obsequious service so annoying in a lot of American restaurants ("Hi, I'm Buffy, and I'll be taking care of you"). For the French, being a waiter or waitress is more like a career than it generally is in the U.S., and they take professionalism very seriously. You don't expect your dentist to say, "Hi, I'm Darrell, and I'll be taking care of your teeth today!" so the French feeling is, why should a waiter be silly and cloying? Service (tips) is virtually always included in the price of a meal in France (that's what the abbreviation S.C. means [service compris], and on some "menus" your beverage is, too, but that's not all that common (it'll say boisson comprise if it is, and there will be a list of choices). Even when service is included, it's always nice to leave a little something, especially if your waiter or waitress was especially good—a couple euros is a nice gesture. No one eats before 7:00, and that's still really early, and not many people really eat before 8:30 in the summer—think more like 9:00 or later. Virtually all restaurants accept whatever major credit card you may have. In fact, they'll have this neat little hand-held thing that they use to process your card; it's totally cool.

One of the things you may have to get used to is how meat is cooked and what you call it. Rare is saignant (saynyanh), medium is à point (a pweinh), and well done is bien cuit (byenh kwee). The thing is, though, is that each of these levels of cooking (cuisson) is about one step rarer than in the U.S. Thus, if you ask for something medium, it'll come a little closer to rare than you might be accustomed to. Rare is really pretty pink, and if you happen to like your meat really rare, ask for it bleu (bleuh)—but know what you're doing on this one, and if you're not hard core, don't try this. Interestingly, for lamb and veal, the cuisson for rare is "rosée."

One of the things you may have to get used to is how meat is cooked and what you call it. Rare is saignant (saynyanh), medium is à point (a pweinh), and well done is bien cuit (byenh kwee). The thing is, though, is that each of these levels of cooking (cuisson) is about one step rarer than in the U.S. Thus, if you ask for something medium, it'll come a little closer to rare than you might be accustomed to. Rare is really pretty pink, and if you happen to like your meat really rare, ask for it bleu (bleuh)—but know what you're doing on this one, and if you're not hard core, don't try this. Interestingly, for lamb and veal, the cuisson for rare is "rosée."

You may also note that if you don't finish your meal/course/whatever, the waiter might asked in a concerned tone whether you didn't like it. In this regard, French restaurants are like your mother—they expect you to clean your plate. But don't feel that you have to. If they do ask, simply say that you've eaten enough ("J'ai assez mangé"), or simply, "C'était bon" (it was good).

And now on to the meat of the matter: click an image below for Tom's favorite left-bank and right-bank restaurants.

Left Bank Restaurants Right Bank Restaurants